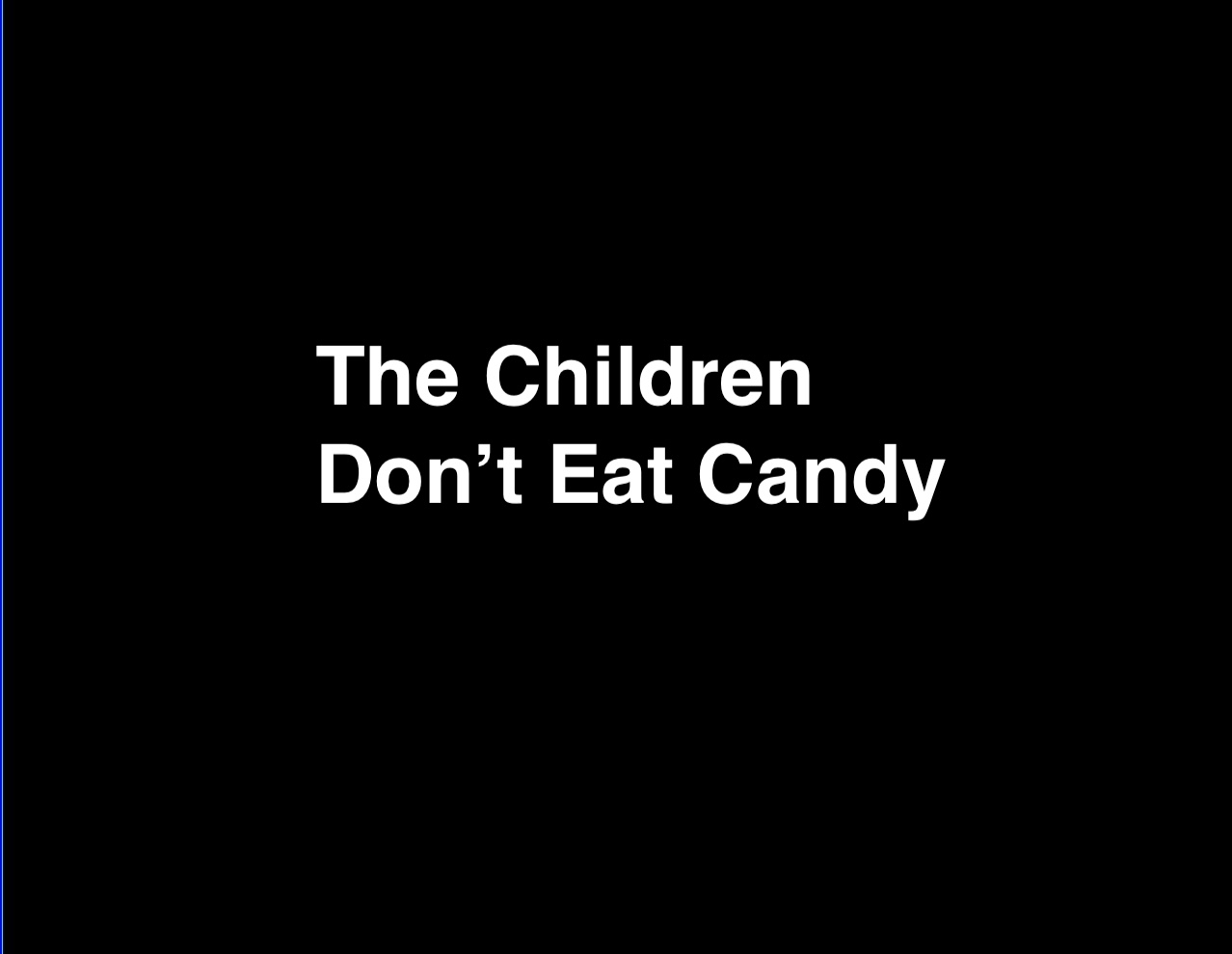

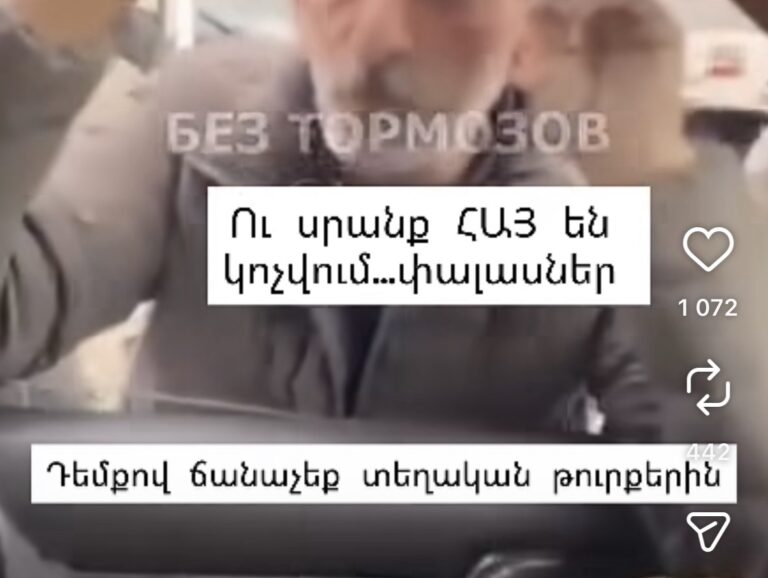

A video recently circulated on social media shows a Kurdish woman and her children living in visible deprivation. Two Ezidi women approach them with clothing, toys and candy however they are met with a woman who, instead of accepting the kind act, asks them if they are muslim and starts to decline the donations when she finds out that they are Ezidis.

This incident is not isolated or new to Ezidis. It is an example of how Kurds have historically treated Ezidis, the very people from whom they (partly) diverged when converting to Islam. The same “original gene,” once part of their community, is now treated as inferior and even dangerous. Similar stories are common among Ezidis. When visiting Muslim neighbors, Ezidis recount that food served in shared dishes (even portions they had not touched!) was thrown away after they left, along with the plates used. The message was clear: in a Muslim social context, Ezidi presence itself was treated as something “unclean”.

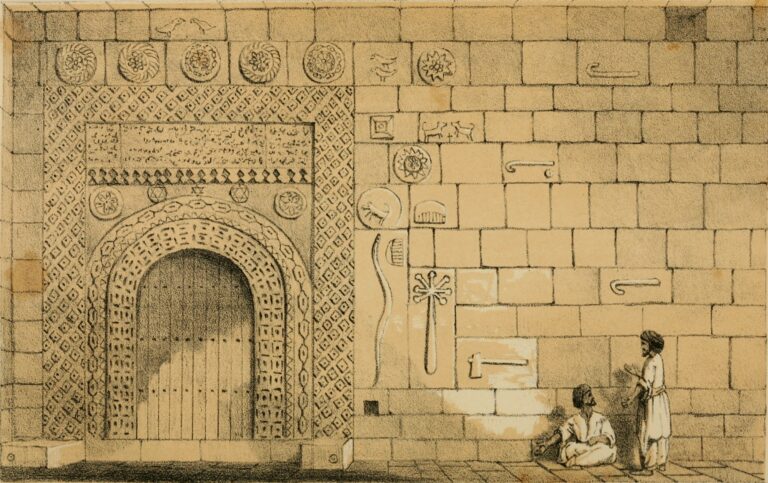

Such behavior does not arise spontaneously. It reflects a deeply ingrained social hierarchy in which Ezidis, adherents of Sharfadin, one of the world’s oldest religions, are treated as morally and socially inferior. This perception has been sustained for centuries and continues to shape everyday interactions for Ezidis.

The logic is familiar. It is the same worldview that enabled the violence and dispossession of 1915, when Ezidis were killed, robbed, expelled from their homes, and had their graves desecrated in search of gold. These were not random acts. They were socially permitted because Ezidis were not regarded as equals.

After the video spread, a second recording appeared in which the woman issued what was presented as “an apology”. Many viewers were unconvinced. The tone appeared forced, the accountability absent. To those watching, it read less as reflection and more as damage control following public backlash.

What the footage ultimately reveals is not individual poverty, but the persistence of hierarchy. Even when Ezidis are the ones offering assistance, they are met with discrimination and hostility. Yet despite the outrageous reaction of the Muslim woman, the Ezidi women in the footage continue to engage, explaining themselves, defending their intentions, and attempting to speak to her with reason.

Ezidis have been discriminated against and it is as if they have become used to it. So used to it that the Ezidi women in the video continue to offer their help, despite being “humiliated”, which is another proof of how humanitarian and kind Ezidis are, even when being offended.

The century long hate and dscrimantion did not end with past genocides (1915), nor with the genocide of 2014. It remains embedded in social behavior, often denied, rarely confronted. The video does not require empathy or excuses. It requires acknowledgment of an uncomfortable reality: anti-Ezidi discrimination is so normalised that even an act of basic human solidarity can be refused — simply because it comes from Ezidis.

To the Kurdish woman in the footage: