Among the most ancient and spiritually profound celebrations in the Ezidi religious (sharfadin) calendar is the sacred feast of Xidir Êliyas and Xidir Nebî. This holy observance reflects the deep spiritual bond between the Ezidi people and nature, agriculture, and divine mercy. It is not merely a seasonal festival, but a living inheritance preserved across thousands of years.

According to Ezidi tradition, the origins of this feast extend back more than four millennia before day one. Many ancient peoples in the Middle East once practiced seasonal rites connected to fertility and agriculture. Yet the Ezidis remain among the few who have safeguarded these rituals with continuity and devotion until today.

Time of Celebration and Spiritual Preparation

Khidir Elias (خدر الياس)

The holiday of Xidir Êliyas is observed on the first Thursday of February according to the Eastern calendar (3rd Thursday according to the Gregorian calendar). The preparations begin on Sunday, the final days of January in the Eastern calendar, and that day is dedicated to purification and cleaning of the home, symbolising spiritual readiness.

This is followed by three days of voluntary fasting: Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday. Although the fast is not obligatory, it is deeply respected. It represents humility, discipline, and preparation for divine blessing. The feast itself is celebrated on Thursday.

During the fasting days and on the feast day, Ezidis traditionally do not travel far from their homes, villages, or cities. The celebration is centered around the household and community. It is also strictly forbidden during this holiday to slaughter animals, shed blood, or hunt. The spirit of the feast is one of peace, life, and harmony with creation.

Khidir Êliyas and Xidir Nebî : The Righteous Servants of God

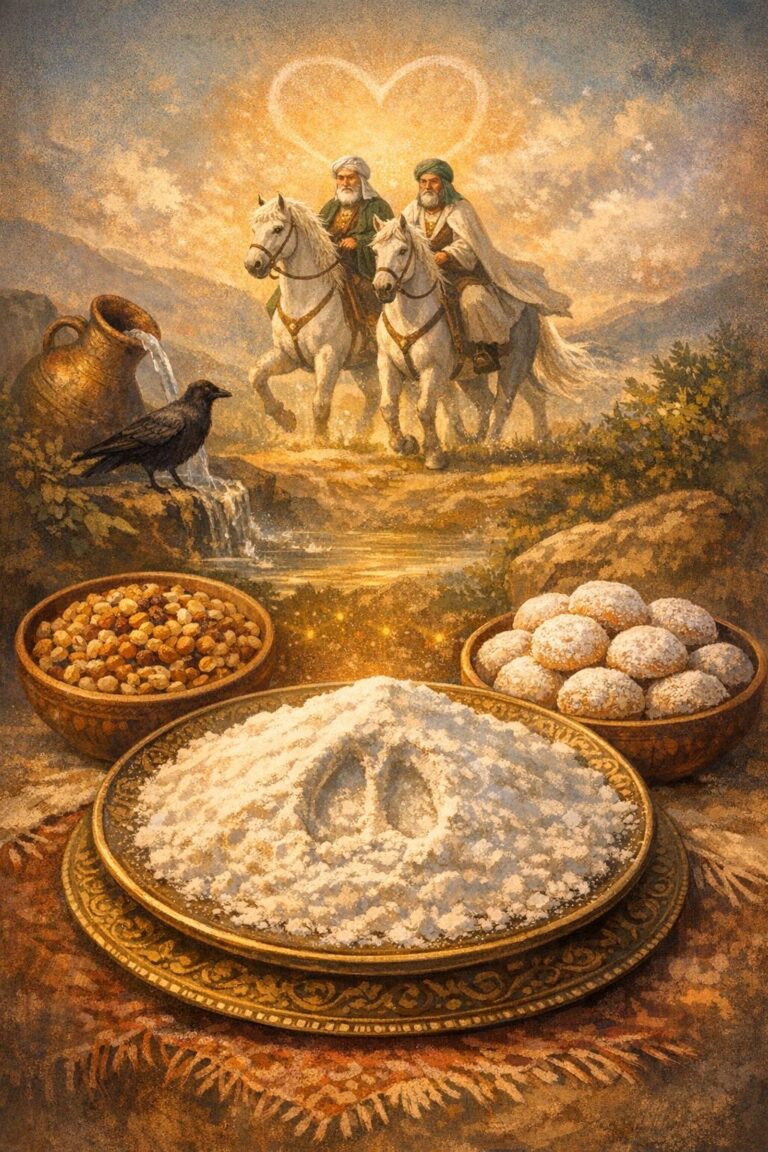

In Sharfadin theology, Xidir Êliyas and Xidir Nebî are regarded as sacred, eternal figures—Çakên Xwedê, meaning the righteous or blessed servants of God. They are understood as celestial beings associated with rain, fertility, agriculture, and divine assistance. Historically, Khidir Elias was known as a guardian of cultivation and rainfall, making this feast inseparable from the agricultural cycle.

The feast coincides with the conclusion of the grain-sowing season. As seeds rest beneath the soil and begin to form roots, the earth enters its cycle of fertility. Thus, Khidir Elias represents divine blessing descending upon the land and awakening it to life.

The Ezidi people hold the names of Khidir and Elias in profound reverence:

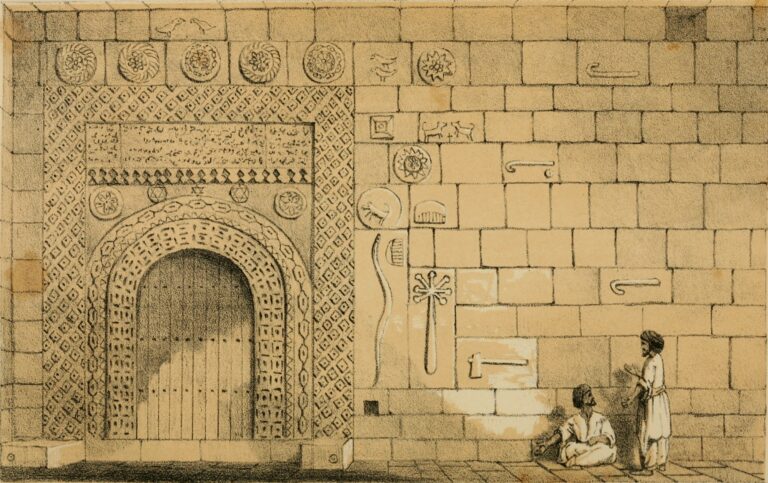

- Temples have been built in their honor, particularly in the sacred valley of Lalish and in Ezidi-inhabited regions.

- Their names are repeatedly mentioned in religious hymns and sacred texts.

- Families invoke their blessing for protection, prosperity, and abundance.

Their importance is expressed in sacred verses (Sebeqe) recited within the Ezidi tradition:

Şerîf dengê kit jî esas e,

Fahmê min zor qesas e,

Tu Xidirî yê an Eliyas e.

Du çavîş li qademgehê rawestiyane,

Ew Xidir e yê dibêjin Eliyas e.

These verses affirm the sacred identity of Khidir and Elias and acknowledge their unified spiritual essence. A traditional saying further emphasizes their presence within the household:

“Xidir Eliyas û Xidir Nebî kesê ne li mala xwe bê behrewî tê de nebê.”

Whoever does not have Khidir Elias and Khidir Nabi in his home shall have no share of blessing within it.

This belief reflects the understanding that a home blessed by Khidir Elias is a home protected and enriched by divine favor.

Preparation of Qelandik (Qelatik): The Sacred Seven Grains

One of the most important rituals of the feast is the preparation of a sacred mixture known as Qelandik. On Monday, Ezidi families, especially women, gather to roast seven types of grains and seeds. These commonly include:

• Wheat

• Barley

• Chickpeas

• Sesame

• Corn

• Sunflower seeds

• Lentils

The grains are roasted, mixed together, and then ground using a traditional hand-operated stone mill to produce flour. The number seven symbolizes completeness and sacred order.

Pekhûn: Ashes of Transformation and Blessing

On Wednesday, part of the mixture is burned and turned into ashes known as Pekhûn.

On the night before the feast, housewives place Pekhûn on a dish and position it near the sacred objects of the home. These sacred objects include an embroidered bag containing holy items, most notably the Berat brought from the holy temple of Lalish. This sacred bundle, known as Qulkiye Berata, is traditionally hung on a wall facing east, the direction of the sunrise.

It is believed that during the night, Khidir Elias may leave a sign upon the dish. If marks appear, it is understood as a blessing, a sign that the household will receive goodness and prosperity.

Farmers also scatter Pekhûn on their fields, seeking fertility, abundant harvest, and divine protection for their crops.

Bi Xwîn: “Without Blood”

On Thursday morning, the ground Qalandok flour is mixed with date molasses (dibs) to prepare the sacred food known as Bi Xwîn, which means “Without Blood.”

The name itself carries powerful symbolism. It signifies that the feast is free from bloodshed and animal sacrifice. It celebrates nourishment derived purely from the earth, grains, seeds, and natural sweetness.

Families eat Bi Xwîn together, and portions are distributed to neighbors, regardless of religious background. This act reflects generosity, coexistence, and social harmony.

Another traditional dish called Çarxos, prepared from roasted and ground bulgur, is also made on the morning of the feast.

Beliefs of Youth and Dreams of Water

Khidir Elias also carries special meaning for unmarried young men and women.

On the eve of the feast, they prepare a very salty bread or dough called Qersik. Each person eats three small, extremely salty pieces before sleeping.

According to Sharfadin belief, if a young person dreams that someone offers them a cup of water, it signifies that love may arise between them and that marriage could follow in the future. Water, in this context, symbolizes life, union, and destiny.

A Feast of Identity and Continuity

Khidir Elias is one of the oldest Ezidi feasts and remains among the most cherished. Despite displacement, persecution, and migration, Ezidis across the world continue to observe its rituals faithfully.

The feast reflects:

• A deep connection to nature

• Respect for agricultural cycles

• Reverence for divine mercy

• Commitment to peace and non-violence

• Preservation of ancient spiritual identity

As expressed by Ezidi community members, this feast demonstrates the inseparable bond between the Ezidi people and the natural world.

Conclusion

The Feast of Xidir Êliyas and Xidir Nebî stands as a sacred celebration of renewal, fertility, and divine blessing. Through fasting, ritual preparation, sacred food, and prayer, the Ezidi people reaffirm their covenant with the earth and with God.

It is a feast without blood yet filled with life.

A celebration rooted in ancient soil, yet alive in the present.

A testament to a people who, despite history’s trials, continue to guard their faith, their land, and their sacred traditions.