This article on the holiday of Xidir Nebî and Xidir Êlyas has been written and shared by members of Yezidi Sarhad. It reflects their research and tradition‑bearing perspective on one of the most significant ceremonies celebrated among Ezidis. For updates and further cultural content, visit the official Yezidi Sarhad Telegram channel here — the primary platform where Yezidi Sarhad members publish insights, announcements, and discussions about Ezidi heritage and spiritual life.

One of the most solemnly celebrated holidays among the Ezidis is the festival (ʿayd) of the saints Xidir and Êlyas (Xidir Nebî and Xidir Êlyas). These saints are revered by many peoples, each holding their own particular understanding of them. Some consider them brothers, others a father and son, and sometimes they are thought to be a single figure. Their veneration is widespread: in Iran, they are called Khizr; the Alawites call him Khawja Khizr; in Azerbaijan, he is Xidir Nebî; in Armenia, he is identified with Surb Sarkis (Saint Sarkis); in Ossetian mythology, he is Vastrdji; and in later periods, he began to be associated with Saint George the Victorious. Notably, Armenians, Azerbaijanis, and Ezidis all celebrate this holiday in winter, mainly in February.

Xidir and Êlyas (Ilyas) are mentioned in Ezidi sacred texts—the Qawls—as well as in folk legends and tales. In the Biblical tradition, stories are told about the prophet Elijah, identified with Ilyas. In Islamic tradition, Ilyas (Ilyas) is recognized as a righteous believer and messenger who called his people to abandon the worship of Baʿal and believe in Allah. They did not heed him and were punished for it. Later, according to post-Quranic traditions, for his righteous life, he was taken by Allah to heaven along with another saint, al-Khidr, with whom he travels the world. The mention of Baʿal in Islamic tradition indicates a link to the Biblical narrative.

The name Khidr (Xidir Nebî literally means “Prophet Khidr”) is believed to derive from the Arabic root kh-d-r, meaning “green,” which some scholars connect to vegetation and the sea. In Central Asia, he is called Hazrat Khizr, imagined as a pious elder bestowing abundance and happiness upon those who see him. In some Muslim countries, he is thought to protect people from fire, floods, and insect bites. The Alawites depict Khidr as a rider in a green cloak.

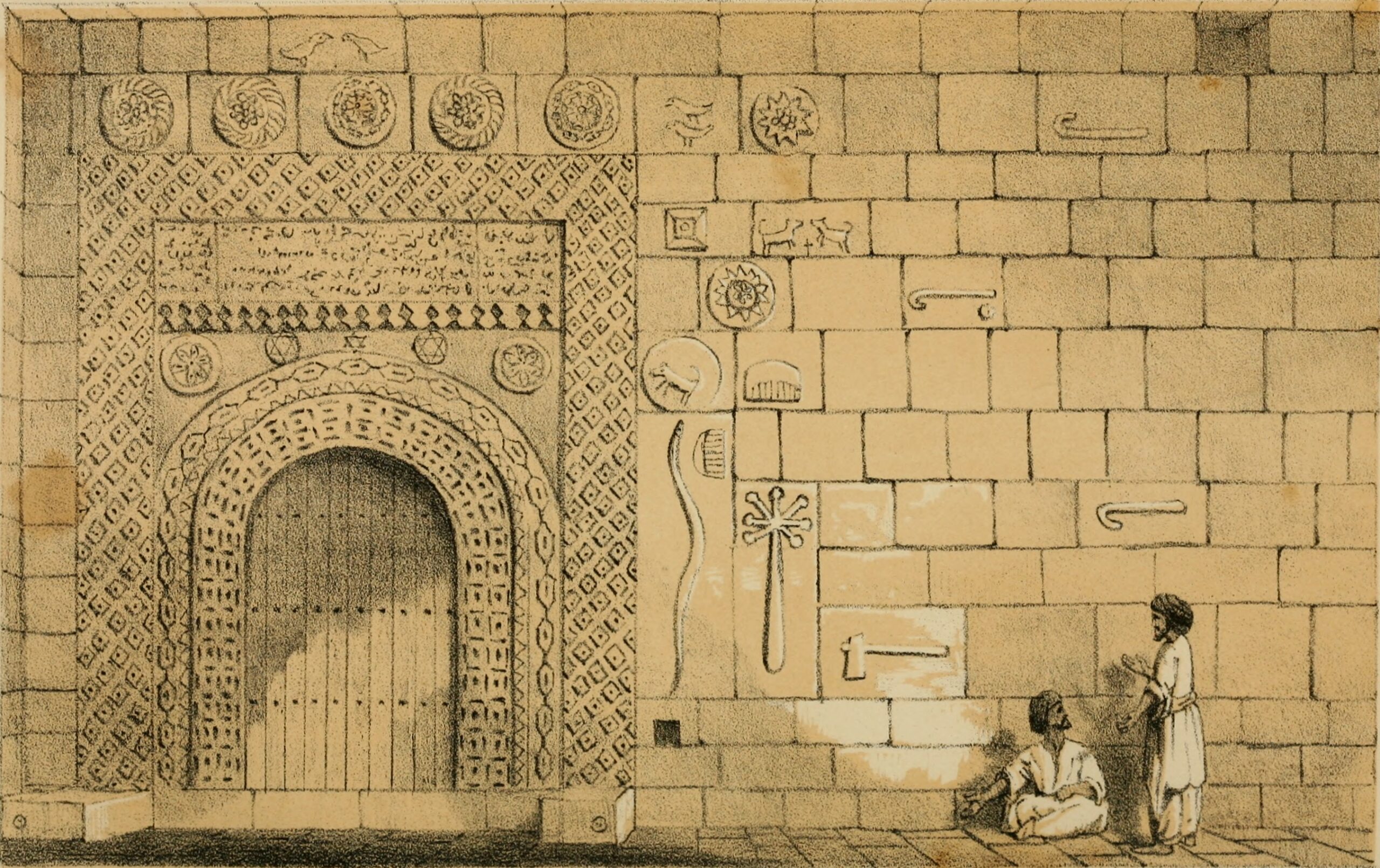

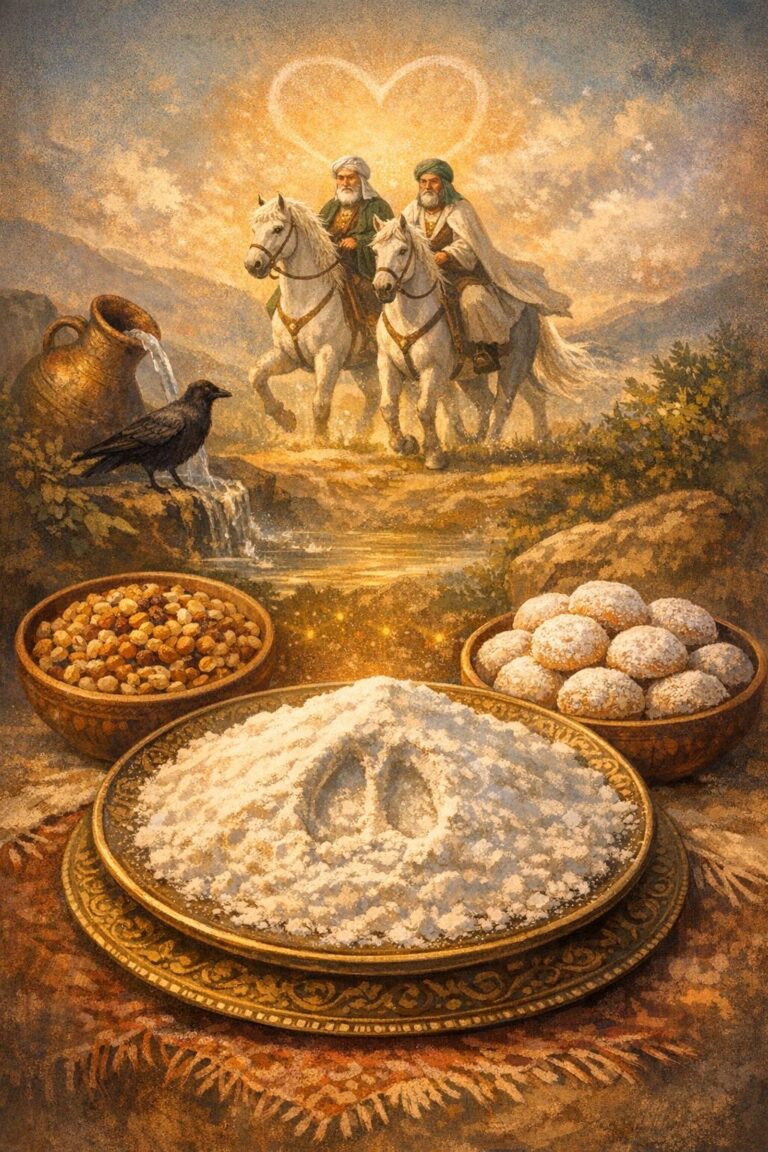

In Sharfadin, Xidir and Êlyas (Xidir Nebî and Xidir Êlyas, sometimes distorted as Hrdailaz or Hrdnabi) are two saints riding a white horse. They are called “Xidir Nebî and Xidir Êlyas, riders on a white horse” (Xidir Nebî û Xidir Êlyas siyarê hespêd boz). The first fulfills wishes and protects lovers, while the second protects travelers at sea. Sometimes they appear as two brothers, sometimes as father and son. Some identify them as a single figure. They are mentioned in Ezidi Qawls, in legends such as About Alexander the Great (Iskander), About Ashiq Harib and Shah Sanam, in the Qawl About Dervish Adam, and other sources.

According to Ezidi legend, Xidir and Êlyas lived in the time of Alexander the Great (Iskandar the Two-Horned), to whom a swift death was foretold. He was told he could avoid death by drinking the “water of life,” which only Xidir and Êlyas could obtain. Following Êlyas’s guidance, Xidir Nebî sets out to fetch the water, facing many trials along the way. He fills a jug and, on the way home, decides to rest under an olive tree, hanging the jug on a branch. While he sleeps, a crow comes, pecks the jug with its beak, and drinks a drop of water. The jug breaks, and the remaining drops at the bottom are drunk by Xidir and Êlyas, who then inform Alexander that the jug has been broken.

Celebration: Traditions and Regional Variations

According to the Eastern calendar (“Old Style”), this holiday traditionally falls on the first Thursday of the month of Sebat (February). It is worth noting that in the rituals of this festival, there are differences between the Ezidis of Georgia and Armenia (descendants of Sarhad in Turkey) and other communities, likely due to geographic distance and historical factors.

One key regional variation concerns the timing of fasting and holiday observances. In most Ezidi communities, the fast is observed on Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday, and the festival (ʿayd) lasts two days: Thursday celebrates Xidir Êlyas, and Friday, Xidir Nebî. In contrast, Ezidis of the former USSR fasted on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday, with the festival honoring both saints on a single day—Friday. Some believers from the former USSR practiced a four-day fast starting Monday, a tradition called bervaçûn, literally “fasting in advance,” implying an effort to “welcome the saints early.”

Three-Day Fast and Restrictions

Regardless of regional differences, the celebration of Xidir Nebî and Xidir Êlyas is always preceded by a three-day fast (rojî), which, like other Ezidi fasts, has specific rules. Believers rise early, before dawn, and after morning prayer partake in the breakfast called paşîv. Then, from sunrise until evening, they abstain from food and drink. At sunset, believers wash their hands and face, pray, and may then break the fast (fitar).

During these fasting days, only plant-based foods—wheat, flour, and dairy—are prepared. It is believed that Xidir Nebî and Xidir Êlyas do not accept sacrifices. Hunting and long journeys are prohibited during this time, as it is thought that the saints themselves hunt, and their work should not be disturbed. However, among Sarhad Ezidis, the strict prohibition of meat was gradually lost, and many believers offered a sacrificial lamb in honor of the saints.

Festive Foods and Symbolism

According to fasting rules, special dishes are prepared for the festival: kiftê den (wheat meatballs), girar (a soup of curd and millet), serbidew, keledoş, hirçik, and qeysî (dried apricots boiled in oil). The central dish is pêxûn (poxîn, qaût), whose name derives from bê xûn, “without blood,” emphasizing the abstention from meat. Pêxûn is made from roasted flour and sugar.

Ezidis in Iraq prepare pêxûn from seven ingredients: beans, lentils, peas, sesame, barley, wheat, and salt (nok, nîsk, baqilk, genim, kuncî, ceh, xwê). These are ground and placed in a corner near the stêr (sacred place in the home). If a horse’s hoofprint of the saints appears on it overnight, it is considered a blessing. Among Ezidis of Georgia and Armenia, it was believed that one could not comb their hair during the fast, as hair would turn into thorny bushes in the path of the saint’s horse, and soapy water into ice, risking his fall.

Love, Blessings, and Festivities

Ezidis in Iraq bake sawik (bread with butter), çerxûş (ground millet), and other dishes. They also distribute qelatîk(roasted wheat) and greet each other for the festival. The last day is called zîpik û qirpik (hail), when they cut hair tips to ensure healthier hair in the coming year.

Xidir Nebî and Xidir Êlyas are considered protectors of lovers and wish-granters, called mirazbexş. On the last day of the fast, young people do not drink water and, after breaking the fast, eat a salty flatbread—totka şor—baked by a prepubescent girl. The bread is split in two: one part eaten, the other placed under a pillow. It is believed that the one who offers water in a dream is the destined partner. The remaining half is placed outside, and the direction in which birds carry it indicates the future spouse.

Among Ezidis of the former USSR, villagers drew symbols in flour on soot-blackened walls of stables. On the eve of the festival (Thursday to Friday), after the fast, people gathered in the house of a sheikh or pir to listen to religious texts and sermons. Then, they visited families who had recently lost relatives, offered condolences, asked for permission to celebrate, and greeted them for the festival. Folk festivities followed, with youth gathering for the dolidang ritual. Dressed in rags, one would glue on a beard and go from house to house asking neighbors to drop something into a sock tied to a stick. They climbed rooftops and lowered the sock through the k’ulek (special light hole), reciting:

“Dolîdangê, dolîdangê, Xwedê xweyîke xortê malê. Pîra malê bike qurbangê: Tiştekî bavêje dolîdangê.”

(“Dolidang, dolidang, May God protect your son, and the mistress [elder woman] sacrifice something. Throw something into the dolidang!”) The one dressed in rags is called K’ose geldî (“the bald one has come” in Turkic). A similar ritual exists among Georgian highlanders, called berikaoba.

Interestingly, this festival is celebrated not only by Ezidis but also by some tribes of Sarhad Kurds. Not all Muslim Kurdish tribes recognize it, viewing it as a remnant of pre-Islamic cults. Mela Mahmud Bayazidi writes: “Fifteen days before the long Armenian fast, Kurds call the holiday Xidir Nebî. Unmarried youth fast for three days; on the fourth, they break the fast but do not drink water. If a boy dreams of giving water to a girl, she will be his wife; if a girl gives water in her dream, it is her destined partner. On the night of Xidir Nebî, they bake pohin (sweet soft pastry made from roasted flour and lots of butter), place it in a wooden trough in the center of the room. The horse of Prophet Xidir Nebî is believed to leave a mark on it, signaling blessing. After the fast, the pohin is made into halva and shared, with some hidden as a symbol of the prophet’s mercy.”

In conclusion, the figures of Xidir and Êlyas (Xidir Nebî and Xidir Êlyas), Surb Sarkis, Vastrdji, and Saint George embody traits of various mythological figures from the ancient pre-Christian and pre-Islamic Near East. Legends of Xidir and Êlyas trace back to the ancient myth of the search for the “water of life,” found in the Sumerian-Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh. Xidir Êlyas is also mentioned in M. Y. Lermontov’s Ashiq-Kerib, recorded from a Turkish-born informant, based on the tale of Ashiq Harib (“the lover who endured hardships abroad”), widespread among Ezidis as a poetic narrative.

To get updates and information about Ezidis and the Sharfadin religion; follow and show your support for the Yezidi Sarhad page on Telegram.