Ezidis in Syria are sounding urgent alarms as renewed fighting, collapsing security arrangements, and instability around ISIS detention camps create conditions eerily reminiscent of the events that led to the 2014 genocide. Across northeastern Syria, Ezidi leaders, activists, and civilians warn that without immediate action, history may repeat itself; this time with even fewer protections in place.

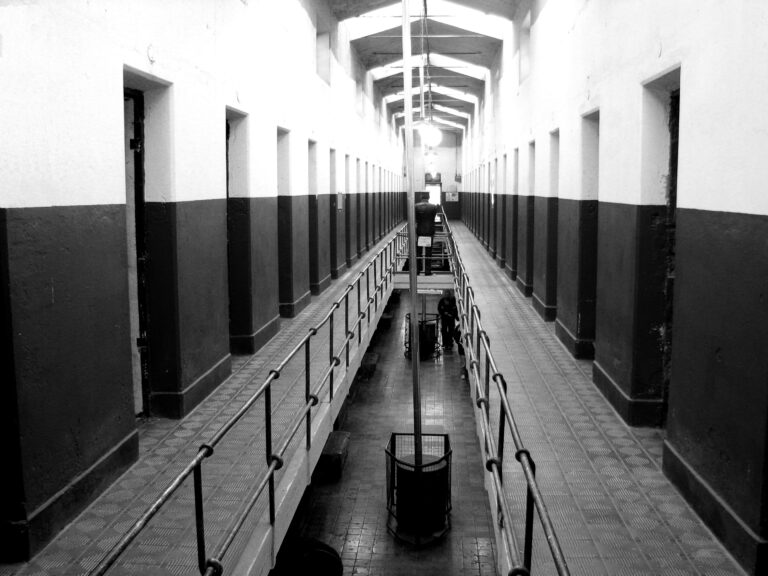

Recent clashes between Syrian government forces and local armed authorities have destabilized large areas where Ezidis live or have sought refuge. These developments have already resulted in the transfer or loss of control over prisons and camps holding ISIS members and their families. Hundreds of ISIS affiliates are believed to have escaped amid the chaos, while thousands more are being moved under emergency arrangements whose long-term consequences remain unclear.

For Ezidis, these events are not distant political shifts but existential threats. The genocide that targeted Ezidis in Sinjar was launched across borders, exploiting precisely this kind of security vacuum. Survivors in Syria and Iraq fear that the same conditions are now emerging again.

Ezidi spiritual leadership has publicly called on regional authorities to secure borders and prioritize civilian protection, stressing that the pain of Sinjar has not healed and must not be repeated in places such as Hasakah, Qamishli, Kobane, or other parts of northeastern Syria. The message has been consistent: armed confrontation brings only destruction, while dialogue and ceasefires are essential to prevent mass atrocities.

At the same time, Ezidi activists have raised grave concerns about women and children still held in camps such as al-Hol. Reports of families fleeing, detainees being released, and extremist ideology persisting inside these camps have intensified fears that Ezidi captives could disappear or be retrafficked amid the disorder. Those who work directly with former ISIS-affiliated detainees warn that premature releases pose a direct danger to Ezidis, especially women.

Displacement is compounding these risks. Hundreds of Ezidis have fled recent clashes in Aleppo and other areas, seeking safety in regions where Ezidis have previously faced harassment, forced religious pressure, and identity-based persecution. Many Ezidis now conceal their faith entirely, fearing accusations, arbitrary detention, or violence simply for being who they are. In some areas, Ezidis report that their religious identity linked to Sharfadin cannot be practiced openly, even in private spaces.

Ezidi women have also become symbolic targets. Recent incidents involving the humiliation and abuse of women fighters, including the cutting of braided hair, have deeply resonated with Ezidis. In Ezidi tradition, braided hair carries profound spiritual and cultural meaning, symbolizing dignity, identity, and continuity. Acts that target this symbolism are understood not as isolated abuses, but as deliberate attempts to erase Ezidi presence and break resistance through gendered violence.

The demographic reality is stark. Ezidis in Syria were already a small population before the war. Today, their numbers have declined dramatically due to emigration, displacement, and fear. Activists warn that ongoing discrimination, insecurity, and the absence of constitutional protections could lead to the complete disappearance of Ezidis from Syria, not only through physical violence, but through systematic conditions that make cultural and religious life impossible.

Ezidis have consistently stated that they seek peace, not war. However, many also stress that past experience has shown that promises without enforcement offer no safety. Forces that previously protected Ezidis from ISIS are being dismantled or absorbed into structures that Ezidis do not trust, while no clear guarantees exist for Ezidi security, recognition, or justice.

The situation in Syria is now reverberating across the border in Iraq, where Ezidis in Sinjar remain displaced, traumatized, and fearful of spillover violence. Survivors and advocacy organizations warn that allowing ISIS networks to regroup, whether through escapes, releases, or neglect, puts Ezidis at immediate risk once again.

Ezidis are calling on the international community to act before it is too late: to protect civilians, prevent further displacement, ensure accountability for ISIS crimes, and recognize Ezidis as a people whose survival depends on concrete guarantees, not symbolic statements. For Ezidis, the warning is clear and painfully familiar. The signs that preceded genocide are visible once more. The question now is whether the world will listen in time.